Insights from the 11th Ohrid Summer School of Architecture and Design – Kuba Snopek

*************************************************************************************

The 11th Ohrid Summer School of Architecture and Design focused on saving Hotel Palas, a modernist landmark in Macedonia that has been closed for years. As an admirer of modernist heritage, I led the Summer School to find new ways to revive the hotel and tackle broader issues of preserving modernist buildings. The following text explores these challenges and the insights gained from our work at the Summer School.

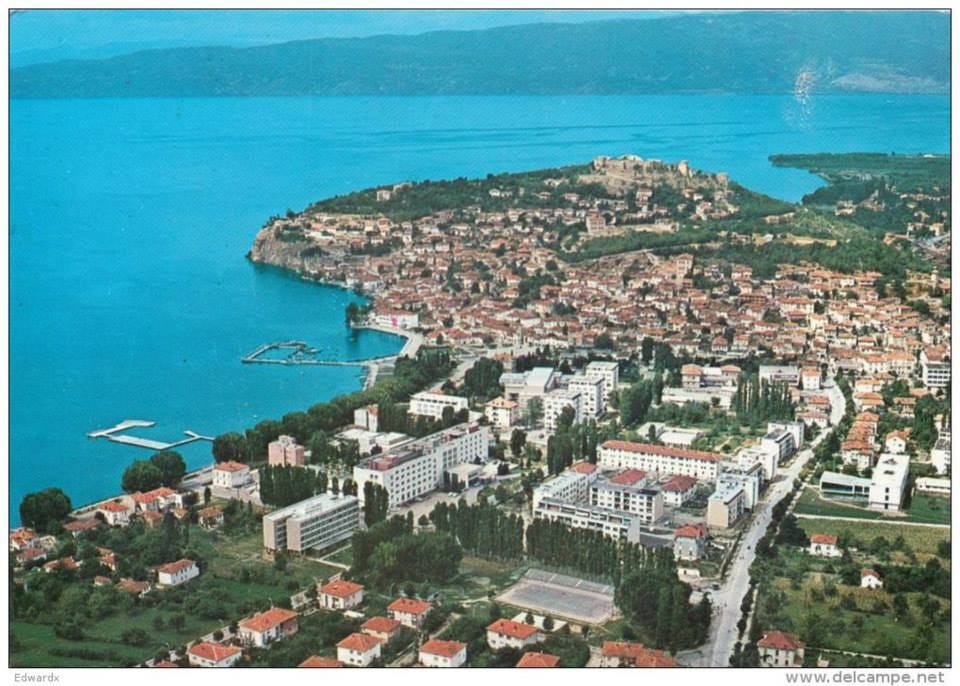

The Ohrid Summer School of Architecture and Design is an annual event held in Ohrid, Macedonia since 2006. Students and foreign professors gather in an ancient city by a magnificent lake to explore architectural challenges. This year’s 11th Summer School focused on Hotel Palas—a modernist masterpiece closed for a decade. The goal was to reevaluate Palas and conceptualize ways to revive it.

I was invited to lead the Summer School due to my long-standing interest in modernist heritage. Over a decade ago, I wrote a book about preserving modernist heritage. Since then, I have repeatedly encountered the same unresolved challenges in my professional practice. How do we convince the public that modernism is heritage? How do we base preservation on authenticity when the original materials don’t last? How do we preserve the social agenda of modernism in a world that no longer shares progressive values?

Modern hotels are especially vulnerable. Being half a century old, they fall into a conceptual blind spot: too old to meet modern hotel standards, yet not old enough to be perceived as heritage worth large restoration investments. Additionally, their simple ownership structure makes them easy to replace. For every modern hotel that was saved, a dozen others have been lost.

How do we base preservation on authenticity when the original materials don’t last?

Those that remain are hanging by a thread of nostalgia. For example, Hotel Uzbekistan in Tashkent. Its elegant concrete brise-soleil facade is now the most recognizable image of the Uzbek capital. However, with the advent of air conditioning, it has lost its function, becoming merely a costly decoration. With substandard hotel rooms, low-quality building materials, and a structure not flexible enough for global reconstruction, what justification is there to save the hotel except for its iconic facade?

Another example is Hotel Cracovia in Krakow. Closed around a decade ago, it cannot reopen as a hotel without major reconstruction to fix the structure. However, this cannot happen because the structure lacks flexibility. The results of last year’s competition to turn Cracovia into a Museum of Design and Architecture clearly showed that such a drastic change of function would inevitably lead to demolishing the building and constructing a replica.

Hotel Palas exemplifies all these challenges. Finding a solution for this building could inspire similar discussions for other similar ones. To tackle this, we assembled an interdisciplinary Polish-Macedonian team. Paulina Paga, an anthropologist, is known for conceptualizing preservation strategies for late-modernist heritage as the director of Lublin’s Museum of Housing Estates (MOM). Pavel Veljanoski and Maksim Naumovski, partners at the Macedonian architectural office k87a and teaching assistants at University American College Skopje, provided profound insights into Ohrid’s legacy and Macedonian culture.

Context

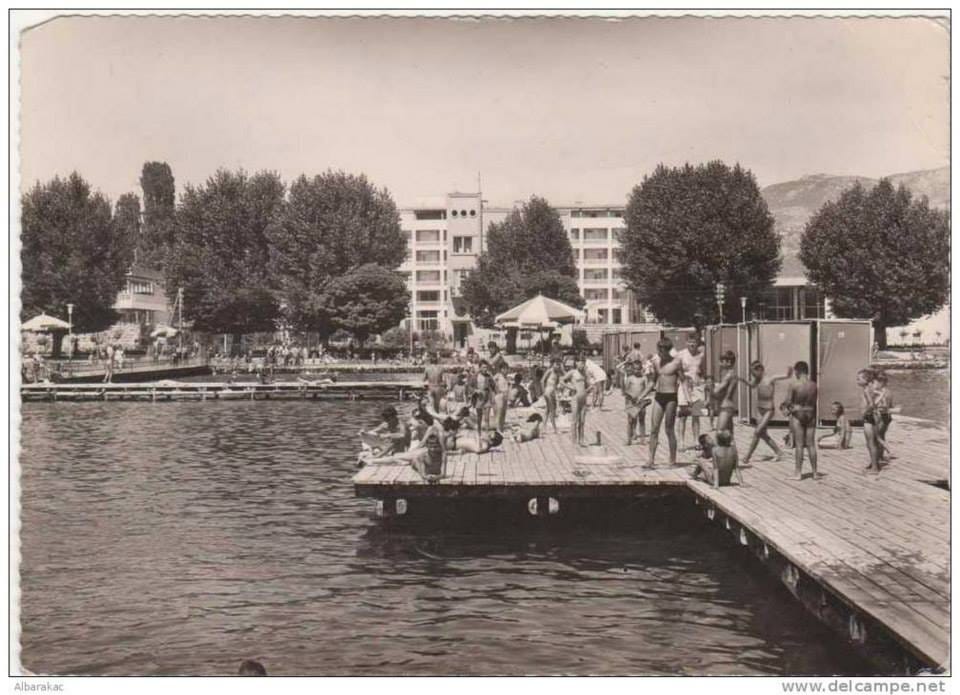

Hotel Palas was built by Edo Mihevc in the 1950s, during the height of modern architecture. Situated between the Ohrid Lake shore and the Old Town, it represented a leap into modernity. Its main five-story section covered by a simple white marble facade housed hotel rooms. Surrounding it were lower sections with lobbies, ballrooms, and other amenities. Palas extended toward the lake with gardens and a public pier.

Over the years, Palas underwent several transformations. A glass-aluminum restaurant was added. The original rooftop terrace was replaced with more rooms. In the 1980s, the lobby interiors got a funky makeover. The pier periodically changed its form and function. The biggest change was not architectural. Originally state-operated and maintained, in 1999 Palas was privatized. By the 2010s, the hotel closed and is now in limbo.

The new owner views Hotel Palas as morally outdated. The rooms are too small, the hotel lacks modern amenities, the ceiling heights prevent air conditioning installation, and the facades do not provide adequate insulation. Fixing these issues requires deep structural changes. And this would be tricky. Palas is non-compliant with contemporary earthquake norms. Built just before the devastating 1963 Skopje earthquake, the hotel’s structure doesn’t meet the updated safety regulations that followed. Improving it to meet these norms would be very costly.

Preservation authorities, however, consider Hotel Palas heritage. One key argument for its preservation is the authenticity of its structure and facade, with a remarkably high percentage of the original 1950s material still intact – unlike many other buildings from the era. Ironically, this same structure does not comply with earthquake norms and makes it impossible to meet modern hotel standards.

This contradiction is at the core of Palas’ problem: morally and structurally outdated, Hotel Palas cannot operate; listed as heritage due to its authenticity, it cannot be rebuilt as the owner wishes. The Summer School aimed to find a conceptual way out of this impasse by challenging either the five-star standard, the preservation norms, or both.

Insights from the Summer School

The core part of the Summer School focused on reassessing the value of Hotel Palas. The students visited the hotel, analyzing its architecture, urban setting, landscaping, and interior design. They reviewed original projects and the changes the hotel underwent, conducted interviews with people who visited during its golden era, and examined newspapers and movies from that time.

The second part involved developing new tools and approaches to redesign, beyond what was previously available. Some students explored existing preservation strategies and the five-star standard, while others investigated the architectural language of Hotel Palas and the possibilities for updating its gardens, interiors, and pier.

Creating a complete preservation strategy was obviously beyond the scope of the Summer School. Such work would take a team of professionals months or years. However, the research produced three major insights. They offer a fresh view of familiar problems and have the power to inspire further discussion.

I. The Palas Universe

The first major insight challenges our approach to valuing and preserving Hotel Palas. It isn’t just another historic building to be preserved for its volumes and facades. Instead, it is a unique and complete design universe in itself – a total work of art blending architecture, artistic elements, interior decoration, graphic design, and landscaping. This rich complexity is exactly what is unique about the architecture of Palas. It is also what creates a palace-like experience that generates the memories driving nostalgia and support for preserving the Hotel.

Preserving this Palas Universe is of national importance. The students discovered that Palas is connected to a broader context. Materials used in its construction came from all over Macedonia. The colors and textures were inspired by local nature, particularly the fauna. Features like the interplay of light, double-height spaces, and chardak-formed terraces reflect local building traditions. Hotel Palas encapsulates the essence of Ohrid City, Ohrid Lake, and Macedonia.

Hotel Palas encapsulates the essence of Ohrid City, Ohrid Lake, and Macedonia.

This finding has several implications for the preservation strategy:

First, the Palas Universe is most vividly expressed in its interiors and gardens, rather than its facades. Authentic interiors on the ground floor should be preserved, including as many original decorative elements as possible. Similarly, the gardens’ aging stone features and the seamless connection between indoor and outdoor spaces – like large windows, terraces, and pergolas – should be protected.

Second, preservation should focus on the current state of Hotel Palas, not just the original design elements. The interior now features at least two architectural styles: the restrained 1950s modernism and the funky 1980s postmodernism. Both styles contribute to a rich palette of colors, textures, and materials. Both are equally important for maintaining the Palas Universe and both should be protected.

Third, this approach does not mean the building should remain static. Instead, it encourages adding new layers in the future that fit within the existing gesamtkunstwerk. This requires codifying the Palas Universe into palettes, catalogs, and guidelines but allows Hotel Palas to evolve and grow more complex and sophisticated over time.

Finally, the student research found fewer traces of the Palas Universe above the ground floor. Compared to the distinctive ground floor, the upper sections of the hotel appear generic and predictable. Unique features such as the Corbusian rooftop terrace and large windows have been lost through various reconstructions. This raises a crucial question: should the focus be on preserving the authentic concrete and steel of the upper floors, or the original intellectual legacy of the ground floor?

II. The Ohrid Pier

The second insight reveals that preserving some of Palas’ public character is crucial; otherwise, its value – both to the community and the current owner – will be lost. Like most modernist buildings from its era, Hotel Palas was created by a state with a socialist agenda. As a result, the building’s progressive ideas are ingrained in its architecture and cannot be separated from it.

From its inception, Hotel Palas was a hub of public life in Ohrid. The hotel was intentionally set back from Lake Ohrid, creating a complex open space that connected the hotel’s terraces and gardens with the embankment and Ohrid city park. This connection was further enhanced by a large public pier extending into the lake.

This urban project, consisting of gardens, an embankment, and a pier, was carefully divided into more public and more private zones, allowing for both integration and separation of people. According to collected memories and historical materials, this thoughtful integration of the hotel with the urban environment served both guests and residents. It created a unique blend of urban and vacation experiences that contemporary hotels cannot replicate.

The hotel’s integration with the city created a unique blend of urban and vacation experiences that contemporary hotels can’t replicate.

The way this space functioned evolved over time. Both the pier, the hotel-to-lake axis, and the boundaries between public and private areas were continually adjusted. What remains clear is that the public spaces surrounding the hotel are essential to its value. The original design cleverly balanced integration and separation. Well-planned open spaces made the hotel an urban destination, while still offering guests the privacy they needed. The pier was the centerpiece of this design, giving guests direct access to Lake Ohrid – the main reason they visited in the first place.

If this nuanced transition from public to semi-public to private spaces is replaced by a simple fence, both the new owner and Ohrid residents will lose something significant. This leads to a crucial insight: any preservation strategy for Hotel Palas must include a shared vision for revitalizing the surrounding open spaces, both public and private. Achieving this would require an active role from the municipality in the reconstruction process.

III. Better to own a Palace than a 5-star-hotel

The third insight focuses on what truly drives value in five-star hotels. While essentials like spacious rooms, high-end furnishings, a wide range of amenities, and top-notch services are necessary for comfort and to stay competitive, the real value driver is a unique experience. This is what will attract high-paying visitors and set a hotel apart from competitors in places like Italy, Croatia, or Turkey.

Interestingly, Hotel Palas already has such a unique feature. Its name is not just a metaphor—the building is literally a palace, though a modernist one. From the high-quality materials and grand ballrooms to the gardens and chandeliers, the architectural style clearly conveys its palatial character.

This design was intentional. The building was created to reflect a social contract where Hotel Palas would ennoble its guests, even if just for a short vacation. As part of their holiday package, guests would enjoy dressing up, mingling in marble interiors, listening to refined music, and sipping elegant cocktails.

This palace-like quality, reflected in the building’s lobby, terraces, and gardens, is what has created lasting memories. There’s no reason why these elements won’t have the same impact today. Therefore, the owner should view creating a precise and nuanced preservation strategy as an opportunity to maximize the building’s value.

Updating the hotel with larger rooms and more amenities is important to meet current standards. However, making the public see the building as a true modernist palace—not just a hotel—is even more crucial. This unique positioning will make the building stand out as a one-of-a-kind experience, regardless of amenities or room sizes.

Owning a true palace—even a modernist one—is more valuable than owning merely a hotel.

Architecturally, this means highlighting elements that suggest prestige and status. This could involve preserving majestic old trees, exposing authentic aged stones, and preserving old pergolas that are gradually overgrown with greenery, turning into a semblance of ancient ruins. Paying attention to these details during redevelopment will be in the owner’s best interest.

A modernist palace is an intriguing paradox. Modern architecture emerged around the same time as European monarchies began to wane. That’s why public perception still ties palaces to historical styles. However, this isn’t entirely accurate. Some socialist countries built palaces for the people: open to the public from day one, designed in a modern style, yet rooted in the long tradition of European palaces. This fact is not widely recognized and limits the perceived value of Hotel Palas.

Changing the mistaken belief that a modernist building cannot be a palace, or that a palace cannot be modernist, can significantly boost the value of Hotel Palas. After all, owning a true palace—even a modernist one—is obviously more valuable than merely owning a hotel.

Conclusion

The goal of the Summer School was to question the key assumptions that have stalled the redevelopment of Hotel Palas. By examining it with fresh eyes, free from commercial interests or Yugo-nostalgia, the students uncovered potential avenues to resolve the impasse.

First, their work suggests shifting the preservation focus from the exteriors to the interiors, and from a literal understanding of authenticity to valuing the uniqueness that comes from the originality of the design.

Second, it challenges the common belief that what happens on private land is none of the municipality’s concern. Ohrid would lose significantly if Palas’s territory were fenced off from public spaces. Interestingly, due to its design, the hotel would lose even more from such a separation.

Third, the building has always been and continues to be much more than just a hotel. Shifting its public perception to make it a source of pride and prestige for both the owner and the citizens of Ohrid is a crucial part of any strategy.

Afterword

I spent a week in Ohrid, talking to architects, activists, students, journalists, and other professionals. Everyone I spoke with about the preservation of Hotel Palas was skeptical. Most did not believe it could be reconstructed without losing its soul or, at worst, being destroyed. I understand the skepticism; success is against the odds.

Over a decade ago, I helped initiate the debate about preserving modernism. My voice was one of many arguing that modernism should be considered heritage, offering ideas on how to achieve this. These ideas from the early 2010s did not stop or even slow the erasure of modernism. Despite these efforts, my city, Warsaw, has since lost almost every modernist building I valued. They were demolished, temporarily dismantled, and never restored, or rebuilt in a way that made them look like parodies. The situation is similarly bleak in other cities.

I see a fundamental reason for this widespread failure: such projects require both public and private stakeholders to work together. Modernism was inherently public, while today’s architecture is predominantly private. The reconstruction must be a public-private effort to preserve value while ensuring profits. Creating a platform for such collaboration and building trust is hard. Finding a business model that supports such a project is even harder. Working out a fair deal that meets everyone’s needs and offsets risks is even harder still.

But it isn’t impossible. In 2023, the Hotel Las Salinas in Lanzarote, designed by Spanish architect Fernando Higueras and built between 1973 and 1977, underwent a significant renovation and rebranding. The renovation involved completely redecorating all spaces and updating the amenities while preserving the original architecture.

The reconstruction preserved modernism for a reason: it was part of the owner’s strategy to build a unique brand. The renovation maintained Higueras’ concrete structure. It also preserved the swimming pool, tropical gardens, frescoes, and sculptures by César Manrique, a renowned Lanzarote-born artist. In other words, the building’s listing as an Artistic and Cultural Heritage site, and its connection to the local culture became part of the business strategy.

The situation with Hotel Las Salinas is unique. It involved an alignment between public goals—preserving the hotel—and business goals—creating a distinctive architectural experience. Most likely, this particular business model won’t work for the hotel in Ohrid.

But others might. I don’t believe in restoring Palas (or modernism in general) to its 100% original state. That would require public ownership and management, which is no longer feasible. Instead, I support a hybrid preservation strategy where modernist components are repurposed for new commercial uses while remaining accessible to the public. Although these strategies are difficult to develop, the results can be astounding when they succeed.

Kuba Snopek is an urban designer and an author of books on art, architecture, and heritage. He is a Fulbright scholar with degrees in Spatial Planning from Wrocław University of Technology, Real Estate Development and Design from UC Berkeley, and Preservation from the Strelka Institute. Between 2018 and 2021, Kuba served as Program Director at the Kharkiv School of Architecture. He founded Direction, a consultancy firm that creates brands, designs destinations, and develops strategies and concepts. Kuba works with public, private, and third-sector organizations, bridging these sectors to deliver new solutions.

Ohrid Summer School of Architecture and Design, founded in 2006, is an annual event by the School of Architecture and Design at the University American College Skopje (UACS). Focused on Ohrid, Macedonia, the Summer School brings together students, professors, and professionals from diverse backgrounds and countries to explore pressing architectural themes.

This year’s 11th edition of the Summer School, held from June 29 to July 6, 2024, focused on reevaluating the Hotel Palas, a decaying architectural masterpiece and national heritage site in Macedonia. Students explored alternative strategies to revitalize the hotel by using its intangible qualities and challenging conventional standards of comfort.

Tutors leading the school included Kuba Snopek (the leading tutor), urban designer and writer; Paulina Paga, anthropologist and founder of the Museum of Housing Estates (MOM) in Lublin; Magda Zaworska, visual artist and landscape architect; and Pavel Veljanoski (Ohrid Summer School program director) and Maksim Naumovski, partners at the Macedonian architectural office k87a and teaching assistants at University American College Skopje.

Guest lectures were given by Ivo Lazaroski and Angela Lekovska. Stefan Zhupan was the official photographer, and Stefan Nazifovski managed the Palas Cinema setup. Other notable attendees included Martin Delovski, Ivan Nikolovski, Goran Patchev, Mishko Ralev, Nikola Duleski, and Nikola Kungulovski.

The students of the 2024 edition of the school were: Anastasija Iloska, Ana Georgieva, Andrej Kostov, Anica Cvetkova, Dina Jovevska, Elena Brzilova, Elena Ogrizovic, Gökçe Uzgören, Hristina Kalkova, Iskra Srnka, Ivana Grupche, Kliment Taneski, Merve Karadaban, Pavlinka Jovancheva, Riste Lelov, Sara Nichota, and Zorica Stavrova.